|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

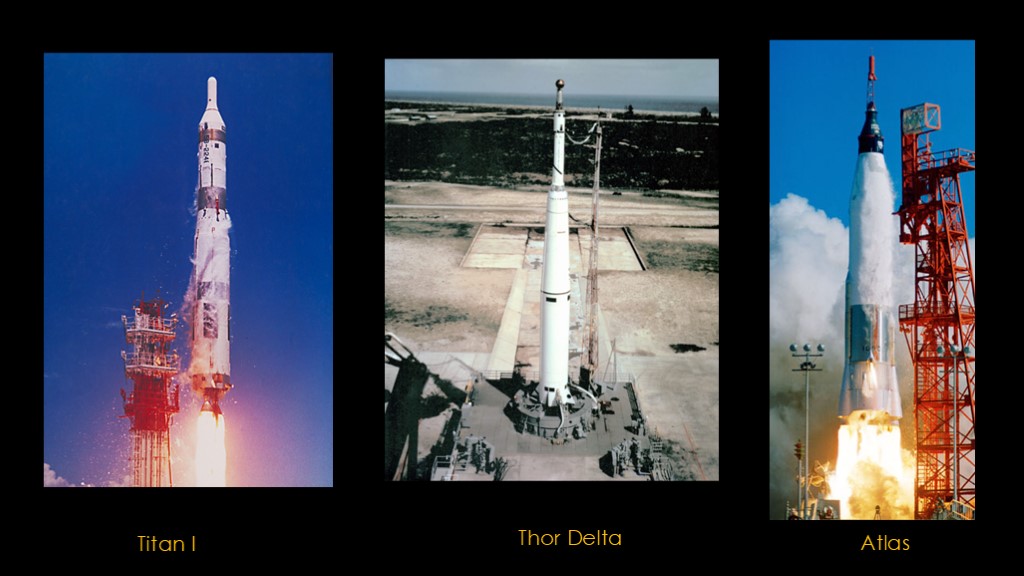

In the 1960s, rocketry was all about missiles - missiles like the titan I, the thor delta, and the atlas.

They were designed for military use and then adapted for scientific use.

But there were others looking at commercial uses for space and an obvious one was communication.

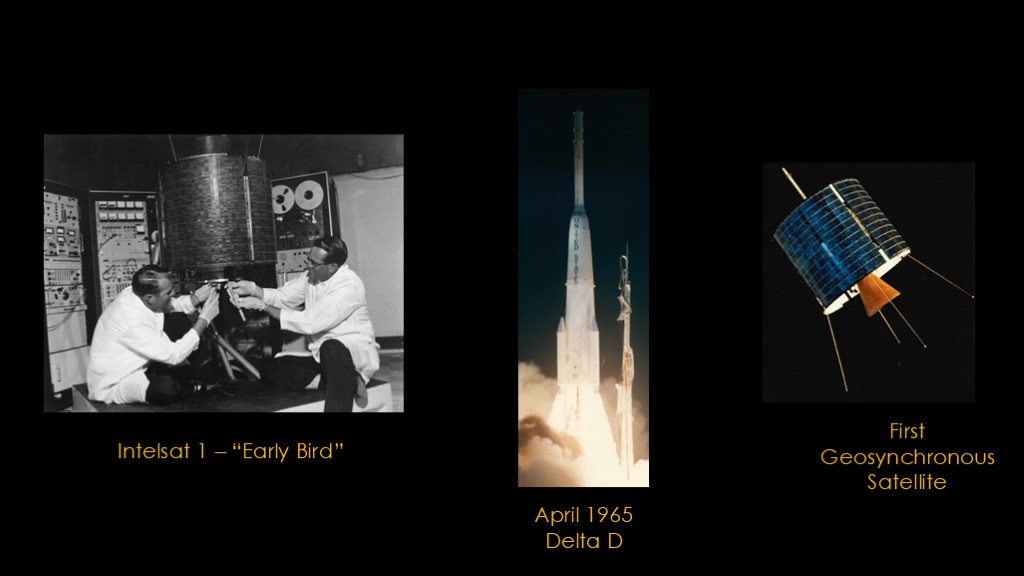

The first true communications satellite was intelsat 1, otherwise known as "Early Bird". It was launched in April of 1965 by a delta d rocket, and it because the first geosynchronous communications satellite.

Satellites in geosynchronous orbit have been the main commercial cargo for many years. And because they are a lucrative market, there has been a lot of competition launching them.

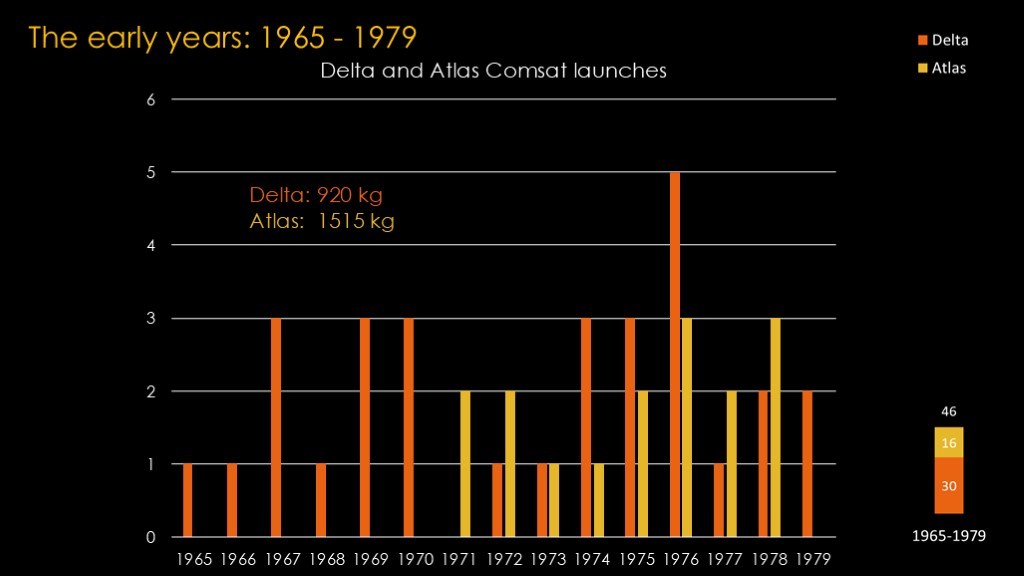

The first few years was all delta, then atlas joined in. During this period, delta launched 30 satellites and atlas launched 16. Delta could launch satellites up to 920 kilograms, and atlas, up to 1515 kilograms.

By the last 3 years of this period, this business had grown to about 20% of the total launch business for both delta and atlas.

It was a good business, and there wasn't any competition. If you were in the west and wanted to launch, you used a US launcher.

But there were two competitors in the wings, one expected, one unexpected.

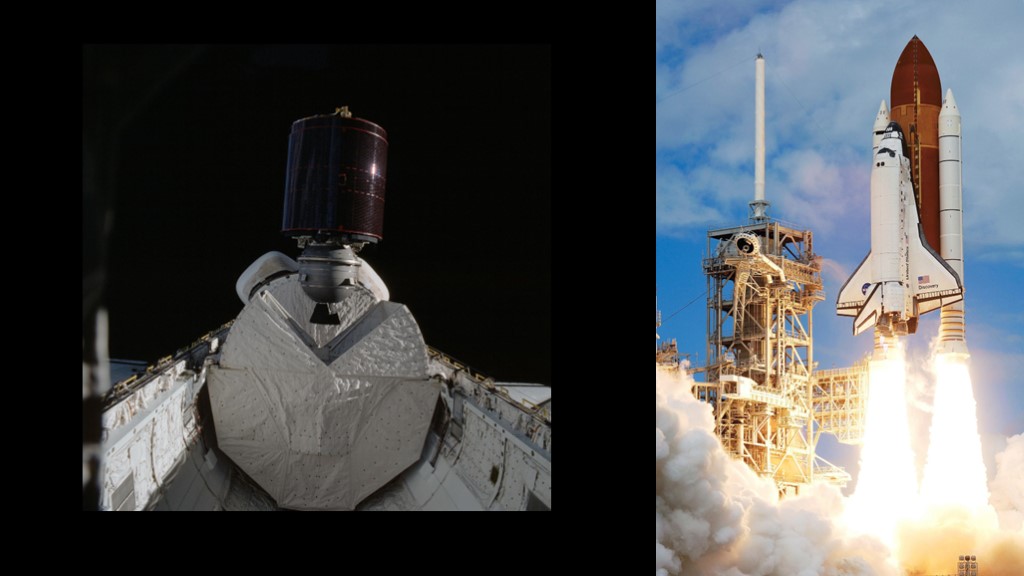

The expected competitor was the shuttle...

The space shuttle was coming and it was going to revolutionize the launch industry. NASA was projecting very cheap flights and the shuttle could carry multiple satellites, each more than 1000 kilograms.

The second competitor was a bit of a surprise.

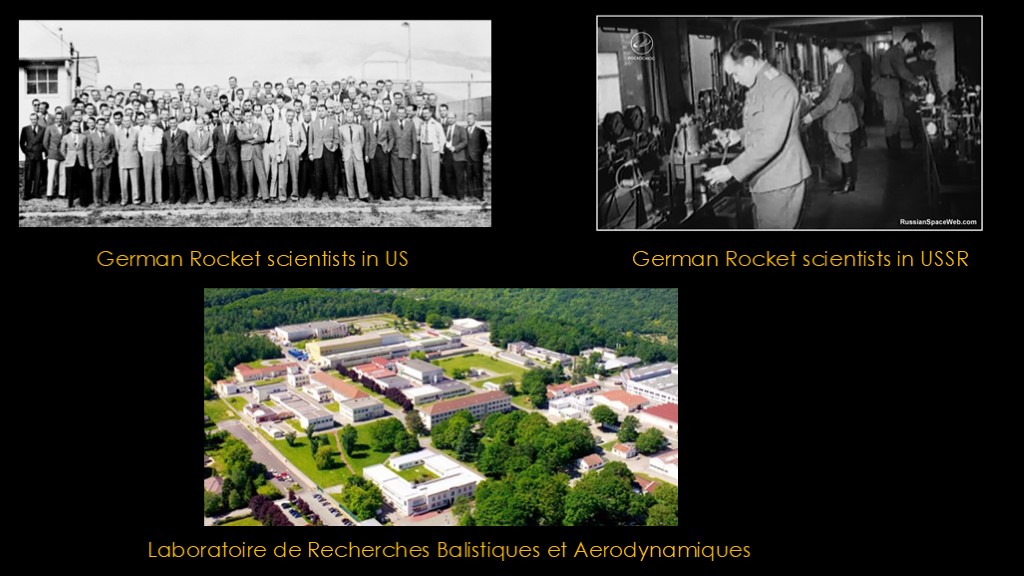

It is very well known that the US recruited a large number of german rocket scientists to come to the US, and the USSR had a similar operation.

What is not well known is that the French also had a program, recruiting 90 scientists and engineers and housing them in Vernon in Normandie.

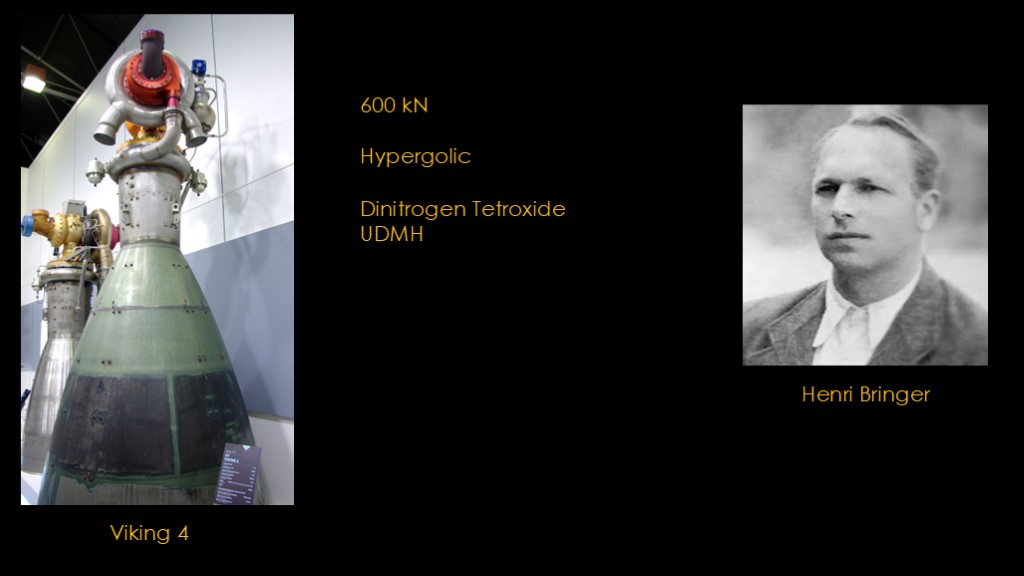

One of the most notable ones was Karl Heinz Bringer, who later changed his name to Henri.

He was the main designer for the Viking engine, a 600 kN engine running on the hypergolic propellants dinitrogen tetroxide and unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine.

This was important because there was a new player in town.

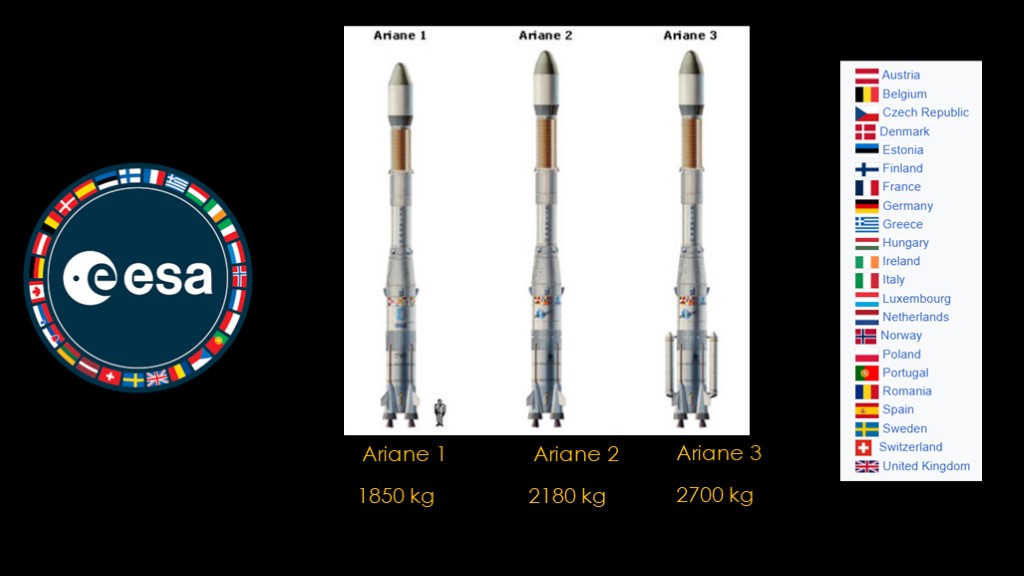

In 1975, a large group of European countries got together and formed the European space agency. They developed a purely commercial launcher named Ariane based upon the Viking engine. Ariane showed up in three variants, with payloads of 1850, 2180, and 2700 kilograms. These payloads were quite a bit larger than Delta and Atlas, and Ariane supported "dual deployment" where two satellites could ride on a single mission and share the launch cost.

ESA had no launch site locations in Europe, so they chose a site at Kourou on the coast of French Guyana. Their site is only 5 degrees north of the equator, so it takes a small amount of propellant to move geostationary satellites to their final orbit over the equator.

Cape Canaveral is at 28 degrees north and therefore launches from there take considerably more propellant to move over the equator.

The launch site location gives Ariane a built-in payload advantage for geosynchronous satellites

The 1980s was an interesting decade.

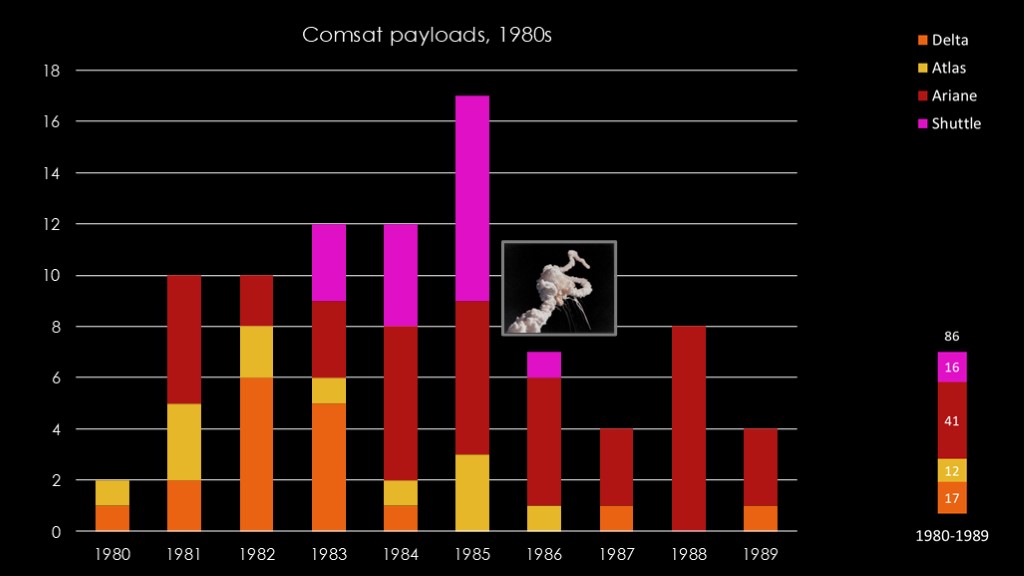

Delta and Atlas kept pace, launching 29 comsats for the decade.

Ariane was very strong, with 41 payloads delivered to orbit. This looked to be problematic for Delta and Atlas.

The shuttle started very strong, with 3, 4, and 8 launches in the first 3 years, but in January of 1986, Challenger blew up and there would be no more commercial satellites on shuttle. Shuttle ended up with 16 total launches.

The launch pace was picking up.

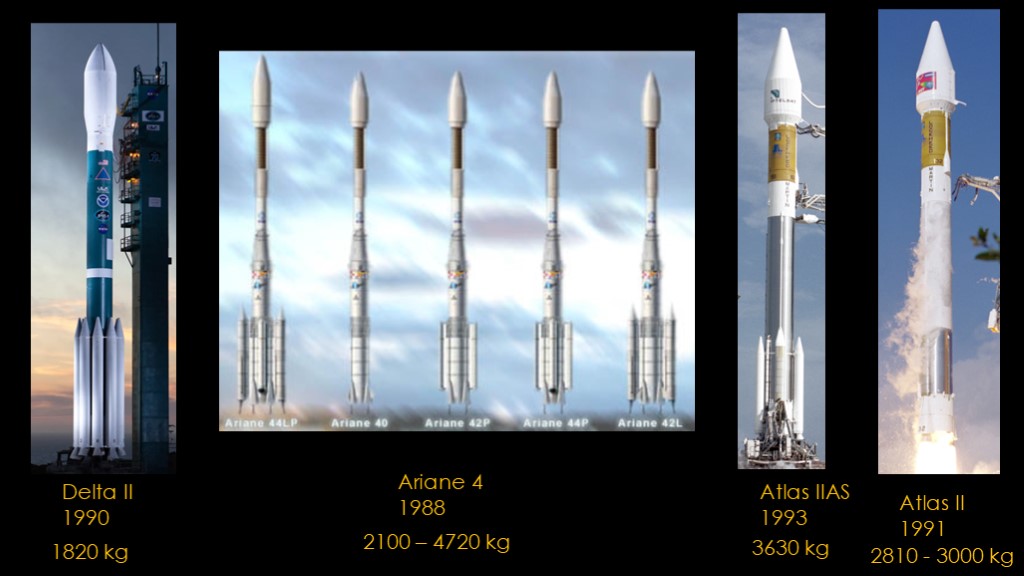

The 1990s would bring three new rockets. The delta 2 would adopt the now familiar central rocket with up to 10 solid rocket boosters, it could launch 1820 kilograms to GTO.

The atlas II would keep a traditional design but debuted the centaur 2 upper stage. The base versions could lift 2810-3000 kilograms to GTO, and a version that added 4 solid rockets pushed that up to 3630 kilograms.

Communications satellites were getting bigger.

Ariane 4 came with a confusing 6 different variants. Not only did is support 2 or 4 solid rocket boosters to increase payload, it could alternatively support 2 or 4 liquid rocket boosters.

The simplest variant could launch 2100 kilograms to gto; the beefiest, 4720 kilograms.

These three rockets competed in the 1990s.

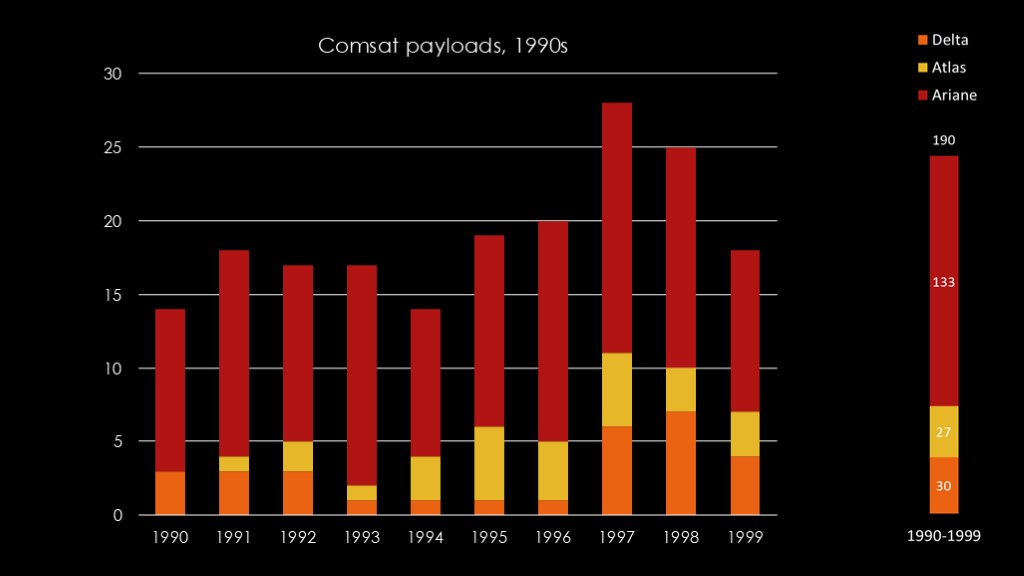

Delta II launched 30 payloads, Atlas II launched 27, and Ariane 4 launched a massive 133 payloads.

There was a problem for the US providers.

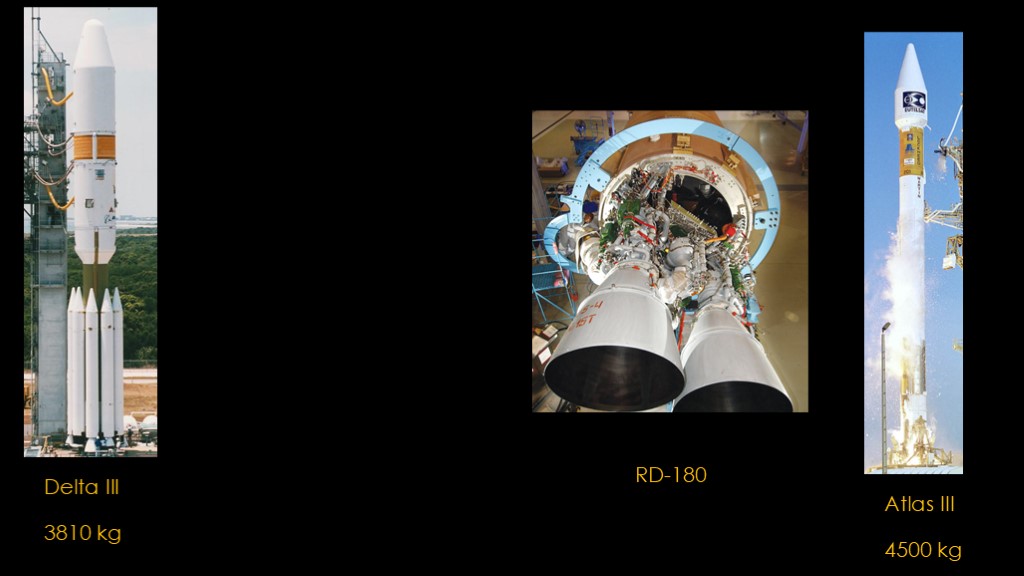

There were a two incremental attempts at fixing that problem. Lockheed Martin created the Atlas III by tossing the Atlas first stage that dated from the 1960s and creating a new one that relied on the Russian RD-180 engine. It had a payload of 4500 kilograms and flew 6 times with 3 communications satellites launched.

McDonnell Douglas came up with the Delta III. They took the existing first stage and booster configuration and built a new high performance upper stage that used liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen.

It was rated to carry 3810 kilograms to geosynchronous transfer orbit, but it failed on its first two launches and did not reach the desired orbit on the third, and was quickly cancelled.

The US department of defense had big plans for space launches and no launcher that met their needs and something clearly had to be done.

they came up with the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program in the mid 1990s. The idea is that the government would contract with one company to build a launch vehicle up to the task and that company would then have enough launches to be able to compete with Ariane in the commercial space. That high launch rate would reduce the price per launch.

There were four bidders - McDonnell Douglas, Lockheed Martin, Boeing (this was before the merger with McDonnell Douglas), and alliant Techsystems, or ATK.

At this point the department of defense awarded contracts to McDonnell Douglass and Lockheed Martin, to the surprise of absolutely nobody. They had decided that two launchers was better than one.

Those two companies immediately cried foul, as their bids had been made assuming they would get all the launches. The DoD resolved this by deciding to give money to both companies for being ready to launch even if they didn't technically perform any launches.

You might think that I'm making this up but I assure you that I am not. For the full story, see "spies, allies, and enterprise - the strange story of ULA.

McDonnell Douglass won with the Delta IV Family, which was based on a new common core using a RS-68 engine and was augmented with 2 or 4 solid rocket boosters in the medium + variant, and three common cores with the heavy variant.

The medium variants could lit 5300-7300 kg to geosynchronous transfer orbit, and the beefy heavy variant could lift 14,220 kilograms.

Lockheed martin won with the Atlas V. It came in a thin 4 meter version with up to 2 solid rocket motors and a thick 5 meter version with up to 5 solid rocket motors. Like the Atlas III, it used the Russian RD-180 engine on the booster stage and a new centaur III for the upper stage. It could lift from 4570 kilograms to 8900 kilograms.

These two rockets together would cover all the department of defense requirements.

Ariane was not standing still, and it developed the Ariane 5, which first flew in 1996.

Like both the Atlas V and Delta IV, it debuted a new first stage, this one being powered by a new hydrogen oxygen engine known as Vulcain and adding in two giant solid rocket motors. The first version would launch 6950 kilograms to geosynchronous transfer orbit, and the later enhanced version would launch nearly 10,900 kilograms.

These numbers were quite competitive with the Atlas V and delta IV.

In perhaps weirder news, Lockheed martin in the US partnered with Energiya and Khrunichev in Russia to create international launch services in 1995. Lockheed martin would bring the Atlas V to the table, and the Russians would bring the Proton, which could carry 6300 kilograms to geosynchronous transfer orbit.

In the 2000s we would have 3 new rockets and one very old Russian one.

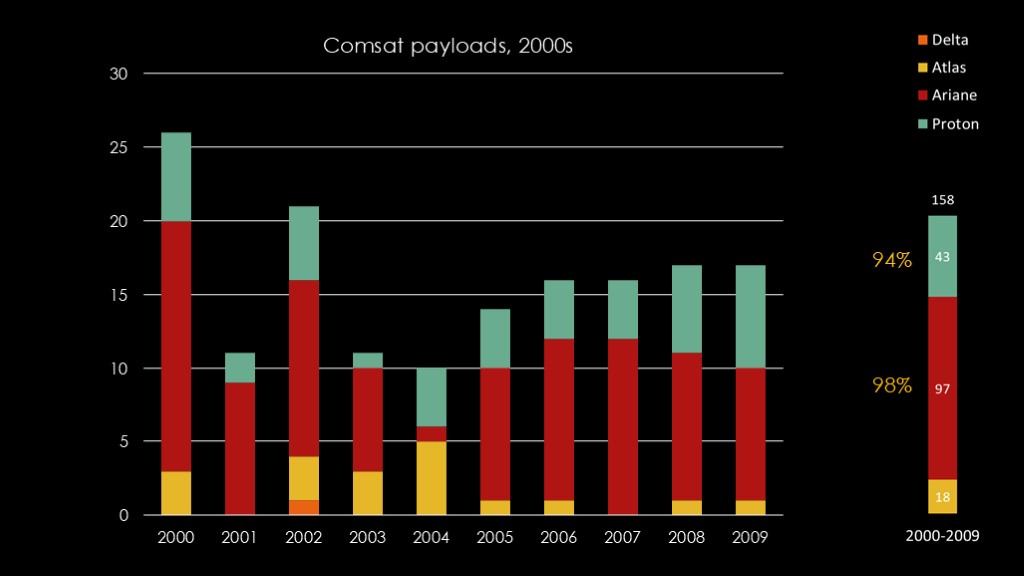

Delta IV was not a competitive commercial launcher. That one launch in 2002 was the only communications satellite launch for Delta IV, and Delta IV M+ launch.

18 payloads for Atlas, most of which seem to have come from the ILS collaboration.

The idea that EELV would result in commercial sales and cost savings doesn't seem to work out very well.

Ariane not surprisingly doing a ton of payloads. The first few years are a mix of Ariane 4 and 5. 97 total payloads for 10 years, which is pretty nuts.

The real surprise is Proton, which hits 43 payloads, nearly half of what Ariane did.

Proton is selling a *lot* despite having a spotty quality record - in this time period Proton had 77 successful flights and 5 failures, for a 94% success rate. Ariane is way up at about 98%.

The higher failure rate means higher insurance premiums for the payloads and a better chance of your satellite failing. Proton's success is a good sign that there is more launch demand than launch slots.

Falcon 9 started flying in 2010, and flew its first GTO payload in December of 2013.

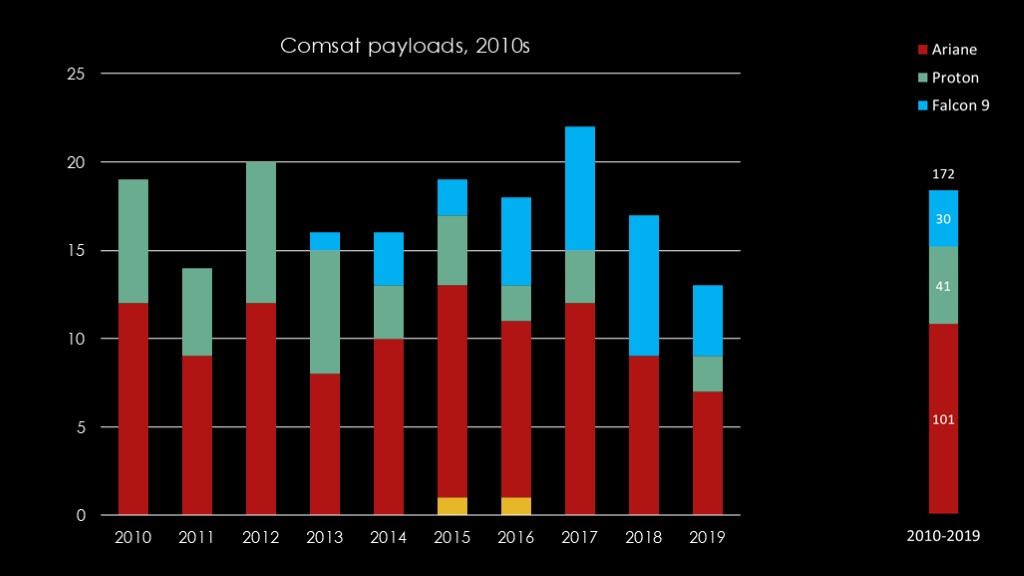

In the 2010s, Atlas pretty much disappears, and Ariane launches 101 payloads. Proton is about the same as the previous decade at 41 launches, but their flight rate went down significantly in the last 5 years when their success rate dropped to 86%

The lack of additional capacity for Ariane and the quality problems at proton left an opening for SpaceX, and Falcon 9 shows up strong, launching 30 payloads over the last 7 years.

That puts the total pretty high, showing that there was a significant backlog at the beginning of this decade.

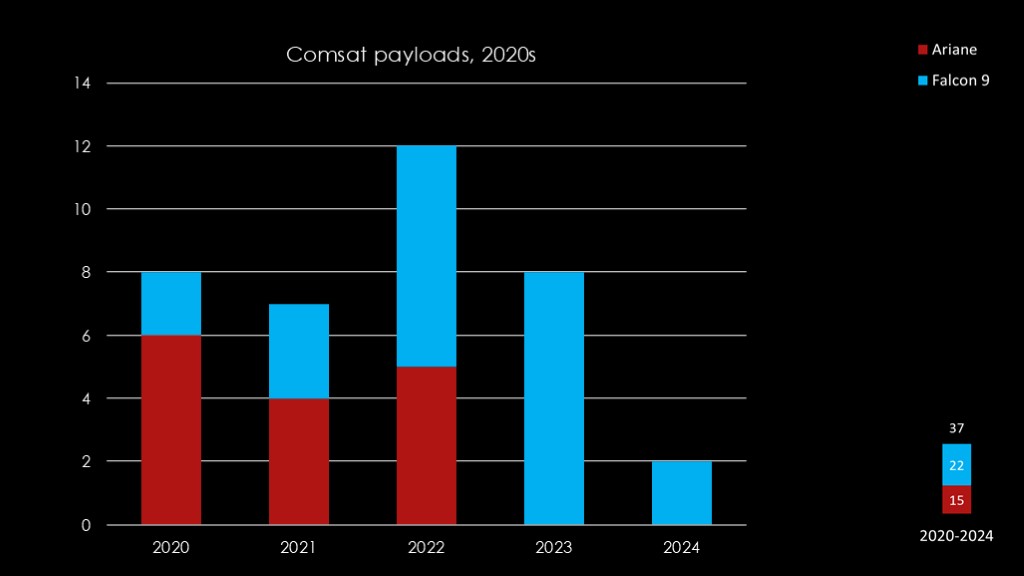

And finally we end up in the current decade.

After 2019, Proton was killed by quality issues and geopolitical issues that made ILS an unattractive option, along with SpaceX providing such good service.

ESA had started work on Ariane 6 in 2015 with a targeted first launch in 2020, but it was significantly delayed and has not yet flown. That left Falcon 9 as the only active launcher for communications satellites and they took advantage of it, flying 22 in the decade so far.

It's obviously true that Falcon 9 Block 5 will continue to launch GTO satellites. It currently has 7 launches on the schedule for 2024.

Ariane 6 is still under development. It is scheduled to launch in 2024 but doesn't have any GTO launches scheduled until 2025.

With the advent of Starlink and other planned satellite constellations, it's not clear what the geosynchronous market will be like in future years.

If you enjoyed this video, please send this T shirt commemorating the launch of Intelsat 3-3 on February 2, 1969 to a geosynchronous transfer orbit.